By Dio Roberson

I’m going to tell you something you already know: every human being is entitled to a roof over their head and a place to sleep at night. This is an indisputable truth, part of the catechism of humanistic virtue. In a world that lived up to its self-professed ideals of opportunity, any condition of homelessness would be rare, brief and non-recurring.

The reality is cultural attitudes toward impoverished people – fueled by toxic portrayals, fear mongering in the media and systematic dehumanization – have made homelessness not a community problem to be solved, but an individual offense to be punished, and defines those who suffer this condition as enemies to the idyllic peace of ‘good (read: housed and well-fed) people’.

Concerns about encampments and other sites where unhoused people make shelter are generally rooted in public safety, i.e unhealthy conditions that may arise in encampment communities, potential for localized crime, and the impact of these conditions on the surrounding community.

But instead of solutions, towns and cities advance anti-camping and public-space ordinances that overwhelmingly punish people who have nowhere to go. The public safety argument positions the rights of homeless folks against the obligation of officials to protect housed people from homeless folks.

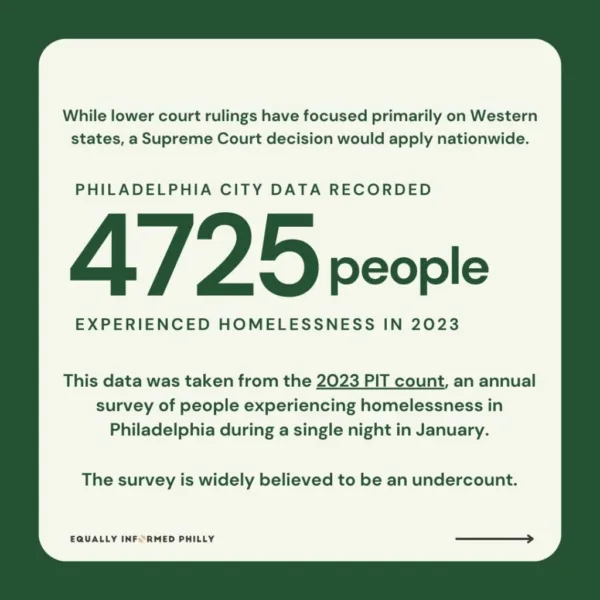

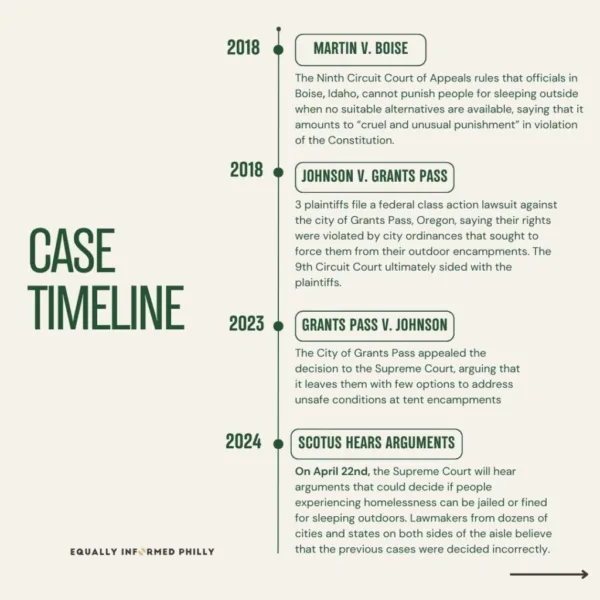

Some western states have pushed this argument all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. A hearing on the 22nd of April could give cities nationwide the license to punish homelessness at their own discretion.

The case originated in 2018, when a group of unsheltered individuals in Grants Pass, Oregon brought a lawsuit that argued the aggressive action and excessive fines that city officials were taking against unsheltered people– under an anti-camping ordinance – amounted to cruel and unusual punishment when the people in question had nowhere else to go.

The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the ruling when Grants Pass appealed in 2022. In spite of city ordinances, an individual cannot be fined or jailed simply for existing in poverty on the streets, they ruled. The upcoming hearing represents a pivotal challenge to that ruling. Because of the potential outcomes on a city-to-city basis, Grants Pass V. Johnson will be the most influential case heard by the Court on the rights of homeless folks in decades.

The number of people who lack stable housing nationwide is approximately 583,000. Of that number, 40 percent, or about 233,000 people, are living unsheltered in places not fit for human habitation (bus terminals, street corners, doorways, etc.). Our slice of that population in Philadelphia is about 4,725 as of 2023, with that figure thought to be an underrepresentation (Facts on Homelessness | Project HOME).

Why It Matters

When my mother, sister and I were shuttling from city to city and shelter to shelter, I learned how shameful it was to be poor and visible. My formative years were underscored by the knowledge that my world defined me as worthless. There was no protection on the streets for me because I was the one who was the threat. People were quick to call the cops on us simply for existing unattractively in a space where we didn’t belong, which I soon realized was any space where good people had to look at us.

While we were much less likely to come to harm in well-lit subway stations, sprawling expanses of public park, or the municipal center of a safe-looking neighborhood, these were the very places we were more likely to be pushed out of by force. As I was told more than once, occasionally by police officers, we were human blights and the clean people didn’t want us there.

Those states appealing to the Supreme Court argue that in the face of alternate shelter options, cities have the right to preserve public spaces for public, not personal, use. In this case, people who refuse places dedicated to serving them are simply occupying public spaces and creating a nuisance by choice.

However, availability and condition of shelters can vary wildly from city to city. Shelter systems that serve huge populations often struggle with funding. And the fact that there doesn’t seem to be a universal standard on shelter adequacy means that cities aren’t necessarily required to maintain the facilities they demand their unhoused populations use.

If we had a homelessness eradication plan that was even a fraction as robust and ambitious as the punitive approach, and provided sustainable housing opportunities and wraparound social services, Philadelphia would have no homelessness issue to speak of. But I’m not holding my breath, considering Philadelphia’s Office of Homeless Services is struggling for resources and the Prevention, Diversion & Intake Unit has no money left in their budget for homelessness prevention services.

I’ve experienced assault, theft, and disease in city-run shelters up and down the Northeast. My mother had to forgo the offer of shelter more than once for reasons of personal health or safety. She couldn’t reject inadequate shelter outright, though – not if she intended to keep her children. She was once offered shelter beds in a facility whose sewage pipes had burst all over and declined with a lie about an option to stay with family in the city. No such option existed, of course, and we spent that night in the bus terminal where it was well-lit, relatively safe and clean.

I can’t imagine any reasonable person not doing the exact same. Unhoused people are forced into choices like this often; however this is exactly what housed folks have identified as an attack on their comfort and, relatable though it may be, doesn’t seem to trigger empathy in anyone.

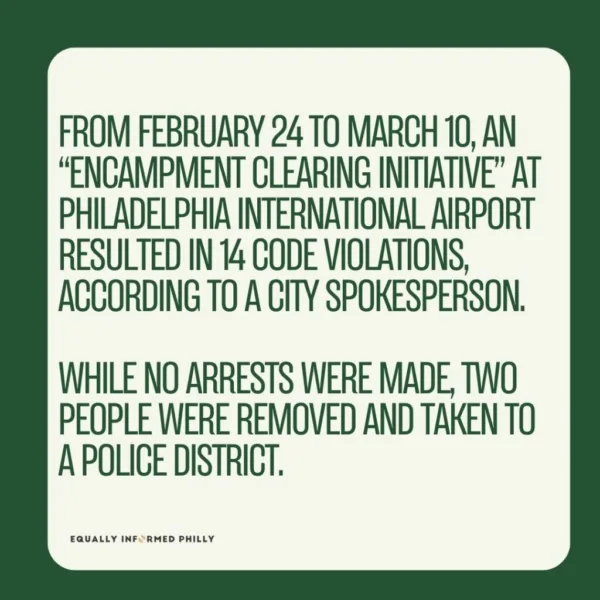

Still every day the Philadelphia government promises to tackle the homelessness issue, utilizing crackdown methods and sweeps – all adversarial moves against our city’s most vulnerable population. Philly promises to remove homeless folks in efforts to clean up the streets, but what do you clean up but garbage? Such language hurts and dehumanizes unsheltered people, makes it easier to enact draconian laws, and reinforces the deep divide between communities in Philadelphia and their unsheltered neighbors.

Apparently, folks can get away with couching truly inhumane language in a theme of public safety. Fear has a way of making otherwise decent people go along with any number of heinous and aberrant things for ostensibly their own protection: ‘us or them’ is a remarkably effective control tactic.

People experiencing homelessness have been denigrated as a group to the extent that obvious dehumanization rhetoric is swallowed wholesale by the decent public. As a result, when folks hear about violent incidents involving apparently unhoused people, such as the shooting on the NYC subway last month, or the killing of Jordan Neely almost a year ago (also on the NYC subway), it reinforces for them that unhoused people are dangerous as a rule. The reaction isn’t empathy for an individual in distress; instead, it’s affirmation of fear – and revulsion – for the vulnerable.

Meanwhile, the statistics on physical harm done to people living unsheltered actually tell a very different story than the going narrative. For example, in 2020 The National Coalition for the Homeless documented 1,852 incidents of violence against people experiencing homelessness at the hands of housed people, over 20 years. At least 515 unsheltered victims were targeted and violently killed specifically because they were homeless.

For My Part

I learned early on that my mother, sister, and I had no recourse when attacks happened – we knew it and our attackers knew it. When your society unanimously agrees that you are subhuman, the “public” in “public safety” simply doesn’t include you.

For Your Part

Philadelphia’s budget for critical services is already strained to the limit across a number of departments; finding more money for entirely new initiatives may be out of the question. But of the millions of dollars allocated to public safety under Mayor Parker’s proposed new budget – some of which will certainly be applied to funding encampment sweeps and punitive action against the unsheltered – the city could potentially redirect some toward homelessness prevention services and shelter resources, which are in dire need. The city stands to make a massively positive impact ahead of the supreme court hearing with a budgetary investment, in earnest, in our existing shelter system. After all, it generally costs governments less money to invest in the lives of human beings than it does to create systems to punish them for suffering.

What message are we sending people when we choose to hurt them in the name of decency, over any of the obvious means of helping them? What are we telling suffering folks when we remain unwilling to entertain any conversation that positions them as community members entitled to dignity and protection? We’re sending the same message I received back in the late 80s, early 90s and mid 2000s: if you happen to slip into poverty, we’ll create one non-life sustaining circumstance after another for you because we’d rather you die and stop bothering us.

And your city officials say they’re doing this for you, good (housed, well-fed) citizens. It’s up to you to speak up and say our government can’t brush aside humans as unworthy….not in your name. If not, then the Supreme Court ruling truly won’t matter at all one way or another; things will stay the same way I’ve always known them to be.

I’ll be waiting, I guess.

This article was originally posted on Generocity with the headline: “When You’re Unsheltered, The ‘Public’ in Public Safety Doesn’t Include You.”

Love Now Media is one of more than 25 news organizations powering the Philadelphia Journalism Collaborative. We do solutions reporting on things that affect daily life in our city where the problem and symptoms are obvious, but what’s driving them isn’t. Follow us at @PHLJournoCollab