The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King once said, “We must develop and maintain the capacity to forgive.”

The Bible says, “If you forgive others their transgressions, your heavenly Father will forgive you.”

And Mahatma Gandhi, the father of nonviolent resistance, once said, “The weak can never forgive. Forgiveness is the attribute of the strong.”

Cheryl Seay isn’t so sure about that.

“For me, I don’t know if I can forgive because when you murder someone, you make a choice to end their life. It’s not an accident,” Seay said. “I know people say if you don’t forgive (the offenders), they have a hold on you. But I don’t feel like they have a hold on me because, without God’s grace and mercy, I wouldn’t be able to sit here and talk to you at all.”

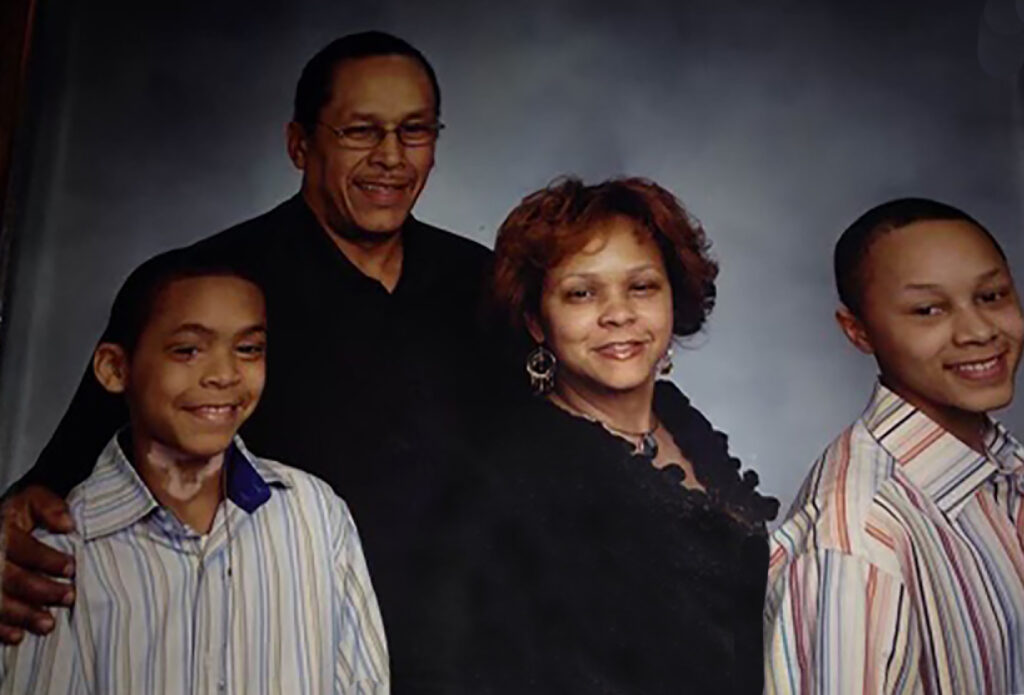

On Easter Sunday, 2011, Jarell Seay, 18, the youngest of Cheryl and Joel Seay’s two sons, was shot twice in the chest and killed on the porch of his West Philadelphia home.

The family had just finished dinner when there was a knock on the door. Joel opened the door to two young men asking to speak to Jarell.

Jarell went out on the porch. Words were exchanged. Then, gunfire.

“It happened so fast, I couldn’t dive in front of my boy,” Joel told a reporter after his son’s murder. “I couldn’t save him.”

The Seays have dedicated themselves to the foundation in Jarell’s name — the Jarell Christopher Seay Love and Laughter Foundation. Its mission is to protect children through gun violence prevention. It is an expansion of the work the Seays did even before Jarell’s murder, by providing underserved children in the community with trips, clothing and school items.

Jarell was one of 324 homicide victims in 2011, and the number of people falling to gunfire has continued to climb. Last year, 516 people lost their lives to gun violence in Philadelphia, and though that number is down 8 percent from 2021, the numbers of lives lost are still unfathomable.

In Philadelphia, gun violence traumatizes victims, their families, the shooters’ families and entire communities. It seems so many people are walking around in a state of depression, navigating PTSD and dealing with various other traumas, that it begs the question: How are people able to move forward?

Many experts point to forgiveness as a key for reconciliation and in some cases, transformation. Philadelphia activist and survivor Oronde McClain was 10 when he was shot in the back of the head almost 23 years ago. He was caught in a crossfire near a neighborhood convenience store. He said forgiving his shooter was crucial to healing, not only for himself but for his community.

Of his offender, McClain said in a recent podcast, “I don’t want you to live your life in fear and be sad and go through depression. And so everybody is affected. So I’m telling you that I understand. I forgive you. Now, you can live your life happy.”

Though forgiveness can be a balm for the community, it is not a requirement in programs that deal with victim violence. As part of its Restorative Justice initiative, the Victim Offender Dialogue Program, sponsored through Philadelphia’s Office of Victim Advocate, offers victims and surviving family members the opportunity to ask offenders about the crime (“Why did you do it?”) and let them know about the harm they’ve caused. It also allows offenders to accept responsibility and recognize the people they have affected.

“The victim and offender both decide how they want the dialogue to go,” Suzanne Estrella, the Commonwealth Victim Advocate said. “A lot of forgiveness is coming out of that program. We see some pretty impactful stories.”

But the push for restoration is always victim-led. For survivors, forgiveness, Estrella says, means “you’re not doing something for the other person, but for yourself. It’s empowerment. You’re no longer carrying the weight.”

But in most cases, restoration doesn’t happen right away. “It’s a journey,” she says.

The act of forgiveness had a profound effect on Jim Hazzard. The West Philadelphian admits, “I was into a lot of wild stuff” when he was a teen in the late ’80s. “I was in the streets and crack was everywhere,” he says.

One of his friends had just gotten killed, so Hazzard took to carrying a gun. One night, as Hazzard and his homies walked to a party, a car rolled up on them.

“Somebody said, ‘duck!’ and it was like, BOOM! It was so fast, I didn’t know I had just gotten shot,” Hazzard said.

About 75 pellets from a shotgun shell splattered Hazzard’s back and arms. He recovered. Five years later, Hazzard came face to face with his perpetrator in the home of a mutual friend.

“I lifted my shirt up to show him I ain’t got (a gun),” Hazzard said. “I said, ‘Yo, I just want to talk to you. I ain’t gon’ do nothing to you. I just want to know why you did it.’”

The offender told him he shot Hazzard on a dare. He and his partners were high while riding around robbing people. His friends dared him to shoot the next person he saw and Hazzard just happened to be that person.

A couple of weeks later, Hazzard ran into his shooter at an arcade. The two embraced, much to the chagrin of Hazzard’s friends.

“For some reason, I didn’t want him to think I was going to do something to him,” Hazzard said. “I would have had to kill him and his friends, and I ain’t no mass murderer. That’s not me.”

The incident marked a crossroads in Hazzard’s life. “That’s the one time I could really say I did the right thing, you know what I mean?” he said. “I’m not trying to live no false gangster life.”

Now 48, Hazzard works security at Bluford Charter School in West Philly. He says he tries to model love in everything he does. With the influx of guns and the senseless violence aimed at them, students don’t know which way to turn, he says.

“A lot of kids don’t know what path they’re going on. They’re scared. Everybody is scared because everybody is on 100 right now–adults too.”

Cheryl and Joel Seay say fear is what caused one of Jarell’s offenders to receive a life sentence — he was too afraid to identify the person who pulled the trigger on Jarell. The person who shot Jarell wasn’t arrested until just before the pandemic hit – after killing someone else in the neighborhood.

What if Jarell’s murderer said he was sorry? Would that be enough for the Seays to forgive?

After a long pause, Joel said, “I would forgive him because I know it’s the right thing to do – because it’s biblical. It’s something I have to do to heal my own self. If I don’t do that, it’s tugging against everything I believe in.”

Cheryl is a little more skeptical. But knowing that systems designed to protect Philadelphia’s children have in many ways failed them, and with the fulfillment she gets working with children through the foundation, her heart softens a little.

She and Joel were in court the day one of Jarell’s offenders was sentenced to life in prison.

“He came to us and said he was sorry,” recalled Joel. “And then he said, ‘I ain’t do it.‘ But he still wouldn’t tell on the guy.”

“Me and Joel actually felt bad for him,” Cheryl said.

Editor’s Note: The Forgiveness Series

Some people find forgiveness to be a vital step in healing and freeing oneself to move forward from the pain of trauma. However, some say forgiveness is not necessary for healing, and instead choose to focus on their own emotional well-being and boundaries as pathways to healing.

Through reporting and poetry, we explore the complexity and nuance of forgiveness, and the impact it can have on our lives, families and communities. From a story of reconciliation to poems that question the concept of forgiveness, this collection offers a diverse range of perspectives and emotions.

We are excited about this thought-provoking and inspiring series on forgiveness and hope it encourages reflection and conversation around this universal human experience.