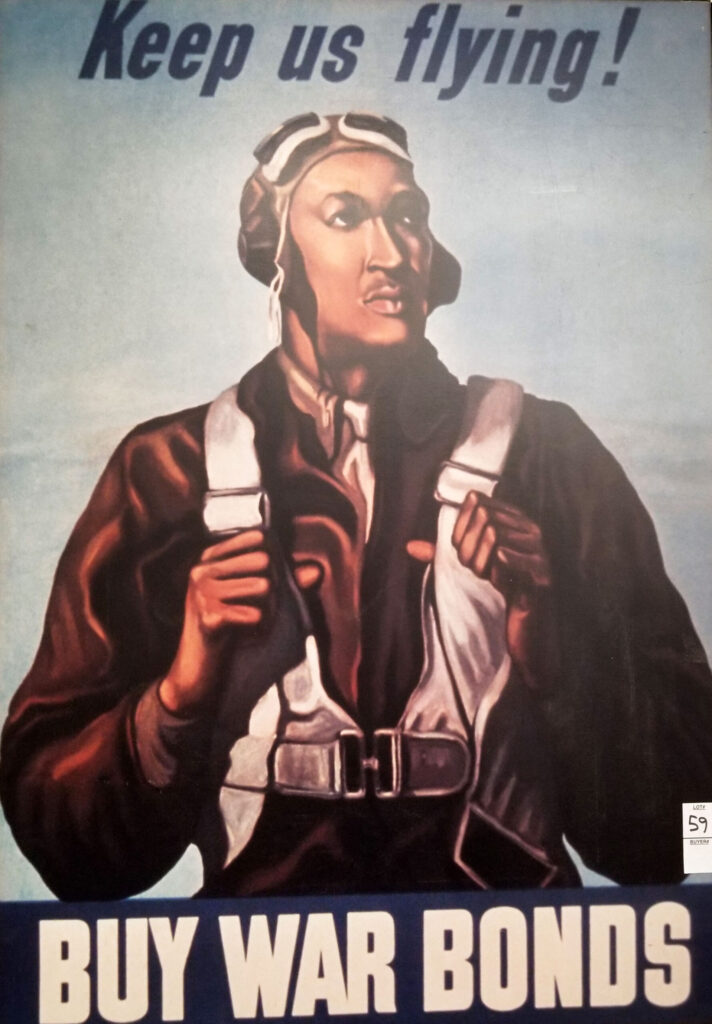

For more than a decade, I have been uncovering the history of Black people from the artifacts and artworks I’ve found on auction tables. They infected me with pride of self, a knowing that all the negativity society associated with people who looked like me were not true. I had proof of our achievements, our lovely brown bodies, our way of living and our defiant nature.

This illustrates the love I found at auction.

Black boys and girls headed to church on Easter morning in 1951 in new coats and shiny shoes. They are serene, their expressions masking the pride and joy in their faces and strides. It is a sweet image of beautiful children.

I found hate in images like the one I will describe but not showcase here.

Naked Black toddlers lying, sitting and crying on the stark outstretched branches of a leafless tree. The 1909 drawing is titled “Blackbirds.”

I choose love.

I’ve been showing that love by sharing and writing about the lives and contributions of Black people as we see ourselves, not someone else’s image of who we are or should be. The “hate” image is what society thought of Black children, their mothers, their fathers, their cousins, their aunts and uncles, and their grandparents for far too long. The “love” photo by Philadelphia photographer John W. Mosley shows how we always pictured ourselves.

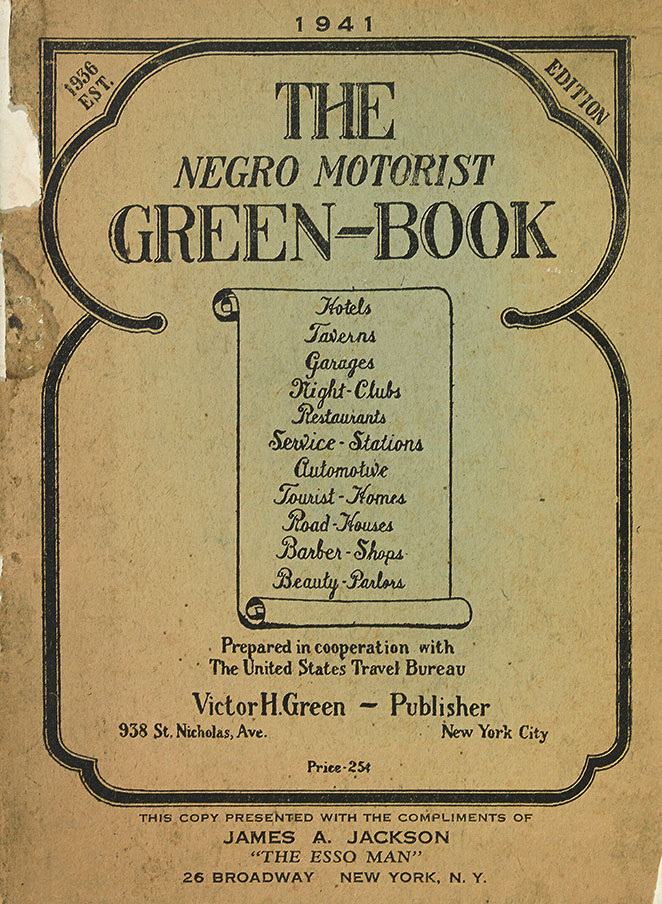

Fascinated, I wrote about our history in my blog “Auction Finds” as a way of sharing with the world what I learned and experienced. I’m doing the same this month when the country – and even Black folks – is focused on 28 days of Black history. I’m compiling 29 days of contributions. I chose an extra day to underscore my belief that our history cannot be chained to a month. Black history extends beyond slavery. We acknowledge it as part of our (and America’s) history, but it is not the start or the sum total of who we are. We should know and feel the part we played in building this country, and that’s why I highlight our history whenever it reaches out to me through time embedded in objects.

I embrace Black history with all my heart. Nothing is more exciting than arriving at an auction house and finding a book about Black doctors in tiny towns in my home state of Georgia in the 1920s, or a poster of the first Black carmaker in the early 1900s, or a flag from a Black Panther Party in Alabama in 1965 before Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale organized theirs in California. Some of that history was hidden inside objects that seemingly had no significance to me: A bright yellow wringer washing machine led me to a Black female inventor who in the 1880s improved on the wringer. She sold the patent to a white man because she feared that white women wouldn’t buy it if they knew she was Black. She was not stymied, though; she went on to her next invention, but it’s not clear what it was or if it was ever completed.

Finding these items and sharing them makes me as happy as the children in Mosley’s photo. There’s a joy in learning more about your people, who had always been told they were not smart enough to fly an airplane or their skin was too dark, or they had no history. Those are myths, and I explode them every time I write about our history and culture.

I want others to be just as knowledgeable and excited about our past as I am. We come from a people who survived within a historical narrative that didn’t even consider us worthy of a footnote. In many ways, we wrote our own stories and continue to do so now. We must look with love and respect at Mosley and the countless others who didn’t let racial prejudice, Jim Crowism and societal indifference stop them. We must absorb our history and gain strength from it. It is one of the ways I choose to love.