By Ryan Moser

The United States leads the world in mass incarceration – one in three adults have been arrested by the age of 23. As a result, as many as 100 million Americans have some type of criminal record.

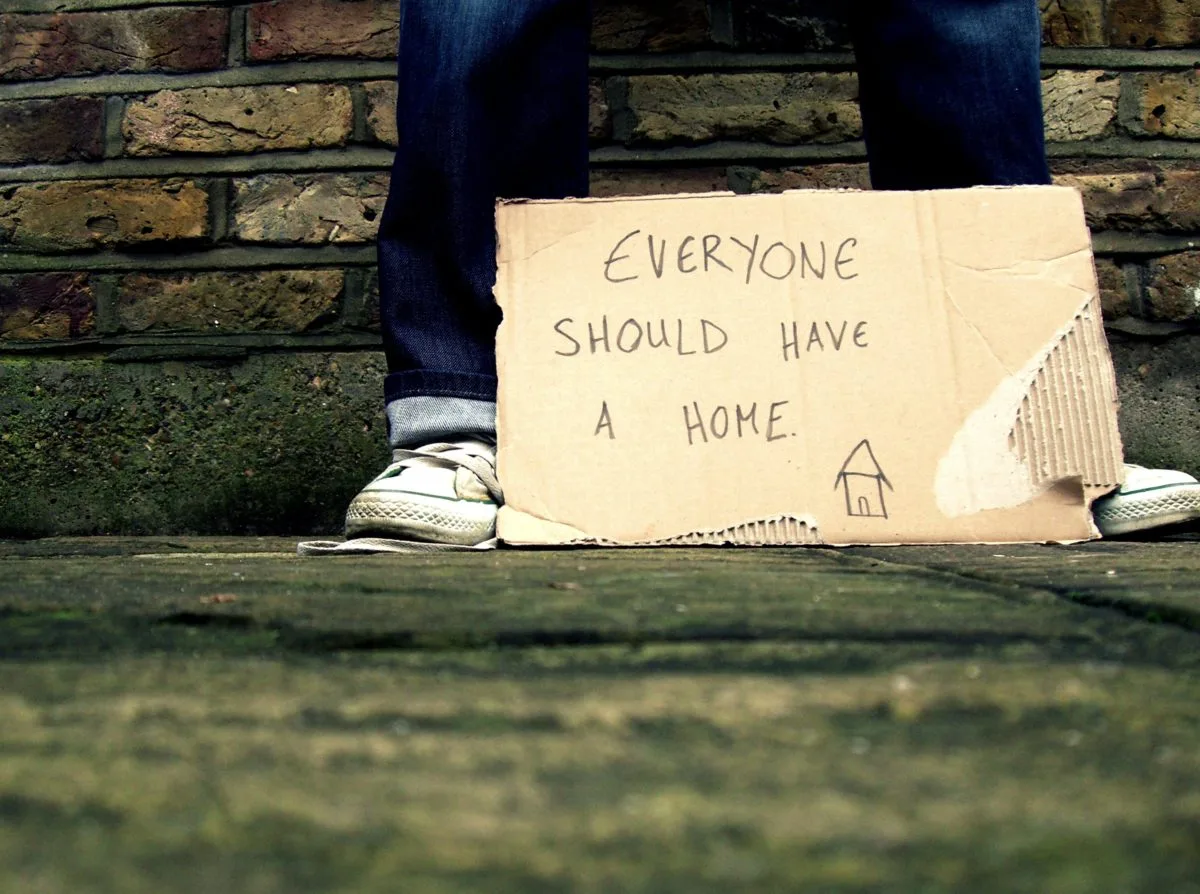

A minor offense or even an arrest without conviction can lead to a lifetime of obstacles. One of the biggest barriers facing a formerly incarcerated person is finding safe housing upon release from prison or jail.

In December 2023, the Philadelphia Department of Prisons had 4,659 incarcerated residents in its custody at four correctional institutions, most of whom will be houseless when released.

“If you don’t have family support in place when you get out, it becomes a dire situation,” said Jonhdi Harrell, director of the Center for Returning Citizens on Broad Street. “The city of Philadelphia can’t provide housing for everyone leaving prison, and there isn’t one private organization that can fill the gap, so reentry housing has often been a do-it-yourself effort.”

While a spokesperson for the Department of Prisons was unable to give a total number of people being released in the county every year, the state of Pennsylvania released around 219,000 people from prisons and jails in 2022, 37,000 of which were women.

Many of these returning citizens exit the justice system not knowing where they’re going to live, making it even harder for them to get a job or go to school.

The options are fairly limited for someone who’s released and doesn’t have a home; transition houses, emergency short-term shelters, and public housing are often difficult to get into, leaving many people living on the streets after their release.

And because communities of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, and people with a history of addiction or mental illness are disproportionately affected by the criminal justice system, it makes the reentry housing crisis not just an ethical problem, but also a social justice issue.

Being houseless has broad implications on a person’s transition from incarceration to their community; it’s nearly impossible to find employment, reconnect with family, or be hygienic when you do not have a place to live.

According to a study done by the Prison Policy Initiative, formerly incarcerated people are almost 10 times more likely to be houseless than the general public. The rates are especially high among specific demographics: people who have been incarcerated more than once; people recently released from prison; as well as people of color and women.

“When I got out of county jail after serving six months, I had no place to go,” said Ron Paige, a resident of the Northern Liberties section of Philadelphia. “I remember asking the guard what I should do and he just shook his head.”

Paige eventually found refuge with a family member, but only after sleeping in a vacant warehouse on Girard Avenue for two nights, just blocks away from a local nonprofit that houses formerly incarcerated people on parole.

After decades of indifference, the Philadelphia Department of Prisons now tries to play an active role in preparing individuals for reentry before they’re released. Regional reentry administrators provide a bridge between correctional institutions and outside organizations, coordinating efforts on a release plan for each incarcerated resident during their last month inside.

Unfortunately, with so few transition houses throughout the city and bed spaces in high demand, many returning citizens without a home go straight into a short-term shelter or the Salvation Army. And while the city offers other public resources to formerly incarcerated people that help them reenter society, there just aren’t enough options for housing.

Limited Solutions and Significant Challenges

In 2019, in order to organize citywide reentry efforts, former Mayor Jim Kenney announced the creation of the Office of Reentry Partnerships, which serves as a hub for referrals and resources and manages initiatives like the Philadelphia Reentry Coalition and Neighborhood Resource Centers.

“This new office represents a renewed commitment to take a hard look at what we can do to support the formerly incarcerated,” said Kenney. “We know that breaking the cycle of recidivism will strengthen neighborhoods, help us decrease our city’s poverty rate, and improve the quality of life for all Philadelphians.”

The Philadelphia Reentry Coalition, a city-funded partner, created an online Reentry Services List that provides information about programs in the city; however, out of the 33 agencies currently listed under Housing Resources, only five offer “reentry specific” housing options, and two of those are just referral agencies. Two of the five only accept women, two more only accept state prison parolees, and one is for single men.

Additionally, the organizations designated as “centralized intake centers for city-funded housing resources”, the Appletree Family Center and the Roosevelt Darby Center, only accept single women and single men, respectively.

One of those reentry specific housing options is Ardella’s House, a women’s advocacy group that helps formerly incarcerated women in Philadelphia by giving them a safe place to live and sleep.

“We have a five-bedroom house for women to go for one-year after they get out,” said founder Tonie Willis.

While the Philadelphia Reentry Coalition website does provide information about the Philadelphia Housing Authority’s successful Second Chance Voucher Program, it doesn’t include contacts for many of the small nonprofits and faith-based programs that offer housing assistance throughout the city, and has had mixed-results.

Therefore, in the sixth largest city in the United States, a returning citizen has little chance of finding reentry housing on what was designed to be the hub for 115 Philadelphia coalition members that includes local, state, and federal government agencies, community-based service providers, researchers, advocates, returning citizens, and faith-based groups.

In response to the lack of transition houses and shelters, some city nonprofits and state officials have advocated for propping up the existing system by renovating vacant homes and renting them at low cost to the houseless, including formerly incarcerated citizens.

“Transition houses are scarce and they’re not always a good environment for growth,” said Harrell of the Center for Returning Citizens. “If we allowed formerly incarcerated people to rebuild the empty homes in Philly and live in them, we’d be teaching new skill sets and solving a reentry problem at the same time.”

According to Billy Penn, a recent city count showed there were an estimated 12,000 vacant properties in Philadelphia. This number includes both vacant homes and vacant lots. In contrast, the number of people experiencing homelessness in Philadelphia is estimated to be fewer than 6,000.

But while a project of this kind has been floated in major cities across the country experiencing a crisis with its unhoused residents, the funding, resources, and community support needed to start have not met the vision.

Furthermore, establishing more transition houses, opening more shelters, and renovating abandoned buildings all seem to be ways to treat the symptoms instead of curing the disease. Without changing the laws that discriminate against people with criminal histories when trying to lease an apartment or home, there will be no long-term solution to the problem.

Reform through Legislation

Pennsylvania state Sen. Nikil Saval (D-Phila) introduced Fair Chance Housing legislation in 2021 to amend the Pennsylvania Human Relations Act to prohibit discrimination against formerly incarcerated people and those with arrest records seeking housing in the state.

Rejected by the majority Republican party, it was strongly supported by colleagues like state Rep. Donna Bullock (D–Philadelphia), who authored a companion legislation in the House, and Philadelphia City Councilmember Curtis Jones, who spearheaded the successful Ban the Box efforts in Philadelphia to expand the city’s fair hiring law.

“This is an issue that makes it hard for people to reintegrate back into their communities after serving their time,” said Saval. “We want to reduce homelessness and help people find stable housing, and that improves public safety.”

In Pennsylvania, a person can be denied a rental property because they were previously arrested or incarcerated in the past, but many people were never convicted or have changed their lives since. Fair Chance Housing legislation would prohibit landlords from inquiring about arrest records of potential tenants as a condition of a lease, and end discrimination against formerly incarcerated renters.

Several states, including New Jersey, California, Washington, and as of December 20, New York, have already adopted some form of Fair Chance Housing in their cities, according to Reuters.

Last March Saval, a minority chair on the Urban Affairs and Housing Committee, reintroduced three bills that would remove inaccurate eviction records from screening reports, create a database to help find affordable housing, and prohibit housing discrimination based on an arrest or conviction record.

“We need to create more opportunities and make ours a culture of second chances,” Saval said. “And the solution is to pass laws that prevent landlords and the housing market from discriminating against people with no basis.”

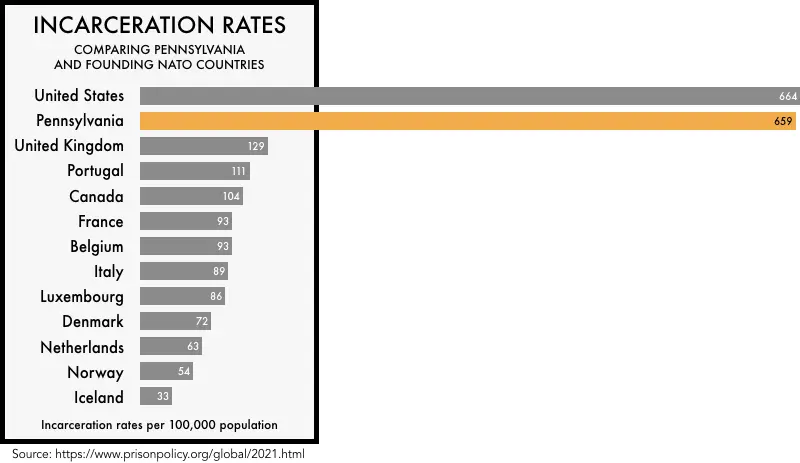

A Prison Policy Initiative study found that Pennsylvania has an incarceration rate of 659 per 100,000 people. That’s about average for the U.S. but far higher than most democratic counties. Neighboring Mexico and Canada, for example, lock up 166 and 104 respectively per 100,000 people. But 95 percent of those Pennsylvanians will come home someday, and one of their first orders of business will be to try and find a place to live.

Many immediately move into negative living situations, have residential instability, or are unhoused; this housing insecurity leads to an unstable environment for anyone, but for a formerly incarcerated person it could mean the difference between success and failure.

Personally Navigating the Housing Hurdle

When I was released from prison in 2022, after serving eight years for a nonviolent property crime that I committed to support my drug addiction, finding a rental home in Greater Philadelphia was the most important factor in my transition plan – and turned out to be the hardest part of rejoining my community.

The first apartment I applied to rejected me without explanation. The second time it happened, I thought maybe I needed to build my credit more. By the third and fourth rejection, and after paying a total of $200 in application fees, I began to think that I was being discriminated against because I was formerly incarcerated.

Four out of five landlords conducted criminal background checks on prospective tenants, and even a minor criminal record can serve as a barrier to both public and private housing. I had a full-time job and savings. I was professional and courteous in my appointments, yet was being turned down everywhere I went.

After one meeting that went exceptionally well, the rental agent inquired about my criminal history, and I gave my typical response: ten years ago I went to prison, but now I’m in recovery and have a support system in place.

“Well you can pay the administration fee and fill out a rental application, but we don’t lease to convicted felons,” the agent said. “Technically, we give all applications equal consideration, but honestly, your neighbors wouldn’t feel safe.”

In April 2022, the Department of Housing and Urban Development published a memo from Secretary Marcia L. Fudge in which she advised her principal staff to eliminate barriers that unnecessarily prevent individuals with a criminal history from applying for HUD programs.

“Too often, criminal histories are used to screen out or evict individuals who pose no actual threat to the health and safety of their neighbors,” Fudge wrote. “And this makes our communities less safe because providing returning citizens with housing helps them reintegrate and makes them less likely to reoffend.”

Moreover, a study by Volunteers of America showed that having a home upon getting out of prison can lower the chances of a person committing a new crime by up to 50%, making neighborhoods safer.

Three months after I was released, I found a privately-owned home where the landlord was willing to rent to me, regardless of my background.

“I’ve been a landlord for 30 years and have had over 100 tenants,” Mike Mattero of Pennsylvania said. “Someone can’t straighten their life out if they have nowhere to live. I’ve given people with a criminal history a second chance and they’ve been a success story.”

But even empathetic landlords can face criticism for renting to someone with a record, despite it being a personal business decision.

“I had to remove one guy after a month because the neighbors found out he had a sex charge,” said Mattero. “My other tenants threatened to move out so I had to evict him, but he wasn’t causing any problems that I know of.”

Other recent initiatives give hope that Pennsylvania will become one of the next states to end discrimination against people with criminal backgrounds trying to find housing, giving hope to some of the 5 million formerly incarcerated people living in America.

Pennsylvania’s Clean Slate legislation is the first of its kind in the nation and enjoys support from both Republicans and Democrats; two different versions of the bill have passed the Pennsylvania House and Senate. Sealed records would no longer be available to the public, meaning that landlords and property managers would not be able to view and hold these records against people seeking housing.

“It’s going to take a lot of work,” Senator Saval said. “We’re getting to a better place, but I think we have to do a lot more to help people when they come home.”

This article was originally posted on Generocity.

Love Now Media is one of more than 25 news organizations powering the Philadelphia Journalism Collaborative. We do solutions reporting on things that affect daily life in our city where the problem and symptoms are obvious, but what’s driving them isn’t. Follow us at @PHLJournoCollab