By Kristin Holmes

We interviewed three dozen people about their vision for a more loving Philadelphia. A common theme that emerged was a call for more investment in young people’s education and mentorships that foster a sense of safety and belonging. People believe this could help prevent violence and promote mutual respect among young people. It has inspired this story’s focus on conflict resolution tools offered in schools that equip students with tools to de-escalate conflicts that result in resolution rather than escalate toward violence. This is the third and final story in our three-part “A More Loving Philly” series.

Philly’s youth are often at the center of news stories. They lead as protesters, activists, and organizers. They disrupt the status quo by riding motorbikes through the streets. They challenge definitions of identity and force us to evaluate whether the world we’ve designed does what it’s supposed to do. Yet, without guidance, support, and investment, youth are critically vulnerable due to a lack of safe places, housing, and education.

“Our kids are left with nowhere to go, which leads them to things like crime…” says Madelyn Morrison, the director of programs at The Attic Youth Center, and “all of the things we mean when we say, ‘I don’t know what we’re going to do with these young folks today.’”

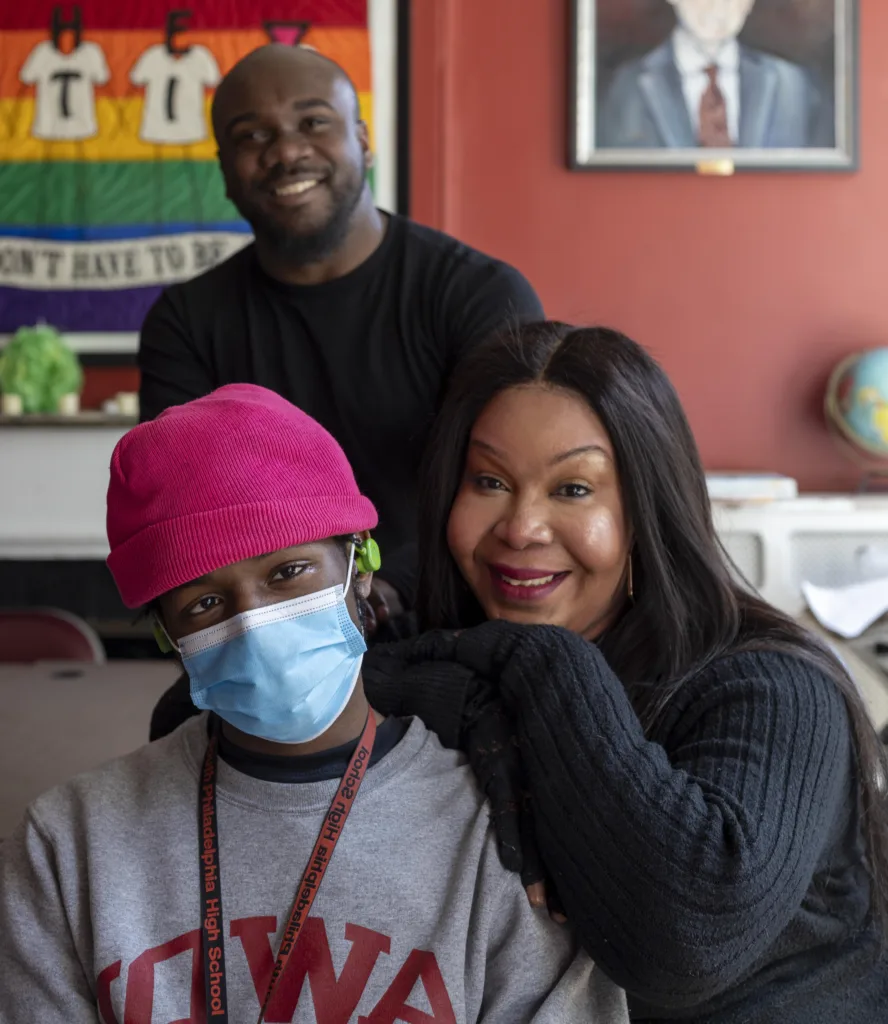

The Attic’s mission is to provide a welcoming space for LGBTQ+ young people, offering counseling, life skills instruction, and other services, but the center’s leaders plan to do more. They have started a program to train the young people who walk through The Attic’s doors seeking safety and support to venture outside the center’s walls and help create the community they want to see.

“I want to teach people respect,” said Brianna Swan, 21. Swan discovered The Attic several years ago when she moved to Philadelphia from a small town in Louisiana where she felt isolated and alone. Part of the lesson Swan hopes to share is akin to a sentiment she once shared with a teacher: “You may not like what I do, but you shouldn’t judge me for what I do or how I look.”

Swan and other young people will be working with The Bryson Institute, a division of The Attic, which offers educational training designed to improve the climate and support for LGBTQ+ people in the places they live and work every day. Bryson has also helped companies develop policies and advised shelters with gender-based challenges.

The Institute has carried out its mission since its founding in 1998. However, executive director Jasper Liem says its leaders are refocusing efforts on involving young people as trainers and incorporating the center’s Youth Leadership Council.

It is an approach to youth empowerment used by The Attic and other organizations that not only strengthens young people to become thriving adults but also provides a skill set and program that will help them transform unwelcoming and troubling spaces into ones that exhibit fairness, safety, equity, and respect.

Morrison describes Bryson’s goal, “It’s not about special treatment; it’s about living regular lives that are seen as lives that are regular.” Morrison is embarking on a youth training program to teach young adults about presentation skills, projecting their voice, crafting a message, navigating Q&A sessions, and ways to deal with online trolls. Young people will train as moderators and participate in mock panel discussions to sharpen their skills.

Their mission will take them to hospitals, corporations, service agencies, schools, and other places where Morrison tells Swan that the young presenter will be ”harnessing the power of their lived experience.”

Layla Ibrahim, 15, of Philadelphia, also believes in using her power to help create healthy spaces. Earlier this month, she led a PowerPoint presentation for a church audience of adults discussing how to make Philadelphia a more loving community as part of a Lenten season message. Lent is a 40-day reflection observed by Christians before Easter. Ibrahim’s presentation talked about exhibiting generosity and kindness and implementing community-based initiatives in a place whose connection to its “brotherly love” nickname she called tenuous.

“The sense of brotherhood that the city advertises itself as having is broken,” Ibrahim said in an interview after her presentation. “When I imagine brotherhood, I imagine people going through life together, supporting each other, loving each other, and people not being forced to go through life alone, even while they are physically surrounded by other people.”

Reducing gun violence is a life-and-death priority, Ibrahim said. Young people and their families must feel safe when they venture outside their homes and should not be secluded inside them.

“We need to be around people, do new things, laugh,” Ibrahim said. “Doing everything behind a [phone or computer] screen or in your home just isn’t enough.”

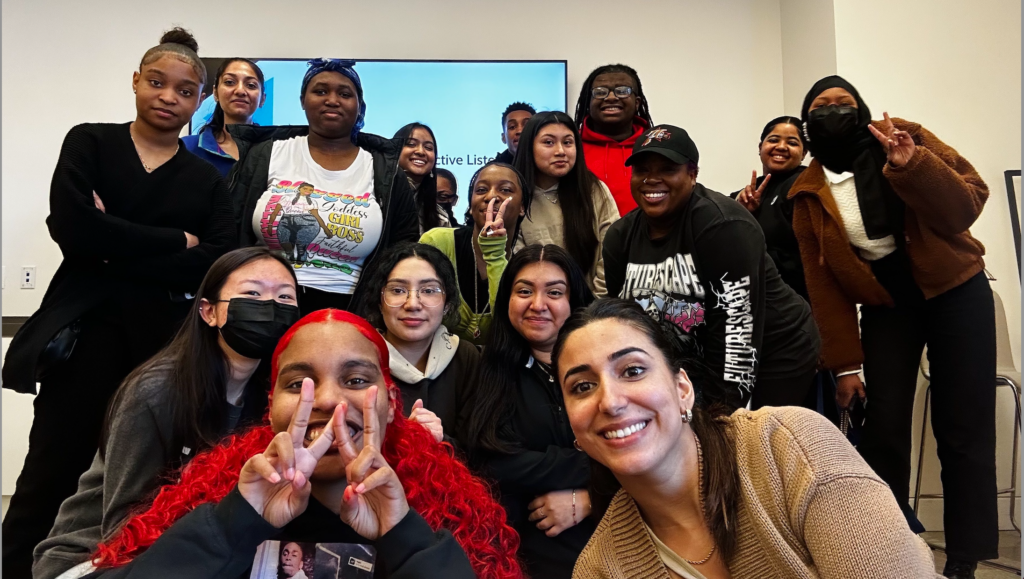

That feeling of connection to a community and the issues that affect it blossomed for 17-year-old Rehanna Griffiths when the student from Northeast Philadelphia participated in a fellowship program with the organization PhillyBOLT (Build Our Lives Together).

The nonprofit works to prepare young people to be leaders and safely work in their neighborhoods to help change them into places that thrive. The group focuses on BIPOC residents in low-income neighborhoods. It offers a special Youth Leadership Fellowship program that doesn’t rely on what they call “outside stakeholders” to drive needed change. BOLT believes young people can do it.

“When we speak to young people, we hear, ‘We are not seen or heard, or we are used as photo ops …’” said Jude Husein, deputy executive director of PhillyBOLT. “What [BOLT] is saying is that there is a need for young people to be not just seen, but to be heard… They are entrusted community messengers. They go home and tell their parents, guardians, and families what’s going on and can mold how families show up in their communities.”

The organization focuses on skill building and then encourages the young person to find a cause and devise a plan to make an impact.

For Griffiths, the issue is youth employment. The Parkway Center City Middle College student helped formulate questions about employment and participated in a youth-led mayoral electoral forum that BOLT co-presented last year at the Philadelphia School District headquarters.

“The issue is important to me because a lot of issues stem from youth not having employment. Too much free time can lead to bad consequences,” Griffiths said. “It would be helpful to have opportunities, learn about resources, and how to find jobs and internships.” She also believes enhanced school programming and surehanded guidance from parents who help their children make the “right choices” are important support systems for young people.

With the help of BOLT, Griffiths says she has begun to believe in her own power. Before she became involved, she described herself as “scared.”

“I was shy. Now, I think my whole personality has changed,” Griffiths said. “I’m more outgoing than I was before, and I’ve learned to speak up for myself and have a say in the issues that affect my community.”

Love Now Media is one of more than 25 news organizations powering the Philadelphia Journalism Collaborative. We do solutions reporting on things that affect daily life in our city where the problem and symptoms are obvious, but what’s driving them isn’t.

Follow us at @PHLJournoCollab