He was 14 when his father was jailed for assaulting the family’s sharecropper landlord during a dispute on a farm in North Carolina.

It happened under the Old Jim Crow laws of segregation in 1952.

His dad, the family breadwinner and protector, was arrested, removed from the home and held two miles away in the small town of Seaboard, N.C.

The arrest and jailing, in front of the teen, would change the family dynamics over the next seven decades.

The boy was W. Wilson Goode, who would later become the first African American mayor of Philadelphia, the nation’s sixth largest city. He would never forget the vision of his dad — his family’s leader arrested and shamed in front of the family, then spirited away in the dead of night to be imprisoned and forced to work for “the state.”

The next time Goode would see his father, the then-49-year-old patriarch — Albert Goode — would be chained and in a striped uniform laboring with a group of convicts on a road not far from the family’s tobacco, cotton and peanut fields.

Goode said his mother, Rozelar, 47, [and his six other siblings] could not run the farm without his father.

“He knew how to farm. None of us knew,” Goode said during an interview in his office in Philadelphia.

The loss of the father cut the family’s moorings, leaving them financially adrift until rescued by a relative who invited them to live in Philadelphia. Goode’s father joined the family in 1954, two years after his arrest.

Goode remembers his dad, a man of hard work and few words, halting the plow and mule one day and saying out of the blue: “‘Wilson, you are going to be someone important one day. People will talk about you.” His father then snapped the reins of the mule and kept plowing without a word.

Goode, who today is an ordained minister, calls his father’s words a “prophecy,” remembered all his life, even when biased school counselors in Philadelphia tried to dissuade him from pursuing an academic track to college.

Nevertheless, the jailing of his dad was a seminal moment for Goode that stuck with him as Mayor of Philadelphia, as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Education under President Bill Clinton, and later as he took the reigns of a budding organization called Amachi (An Ibo word that means “what God has brought us through this child.”)

Through Amachi, he has helped 350,000 children like himself who have become collateral damage to parental incarceration – most of them fathers.

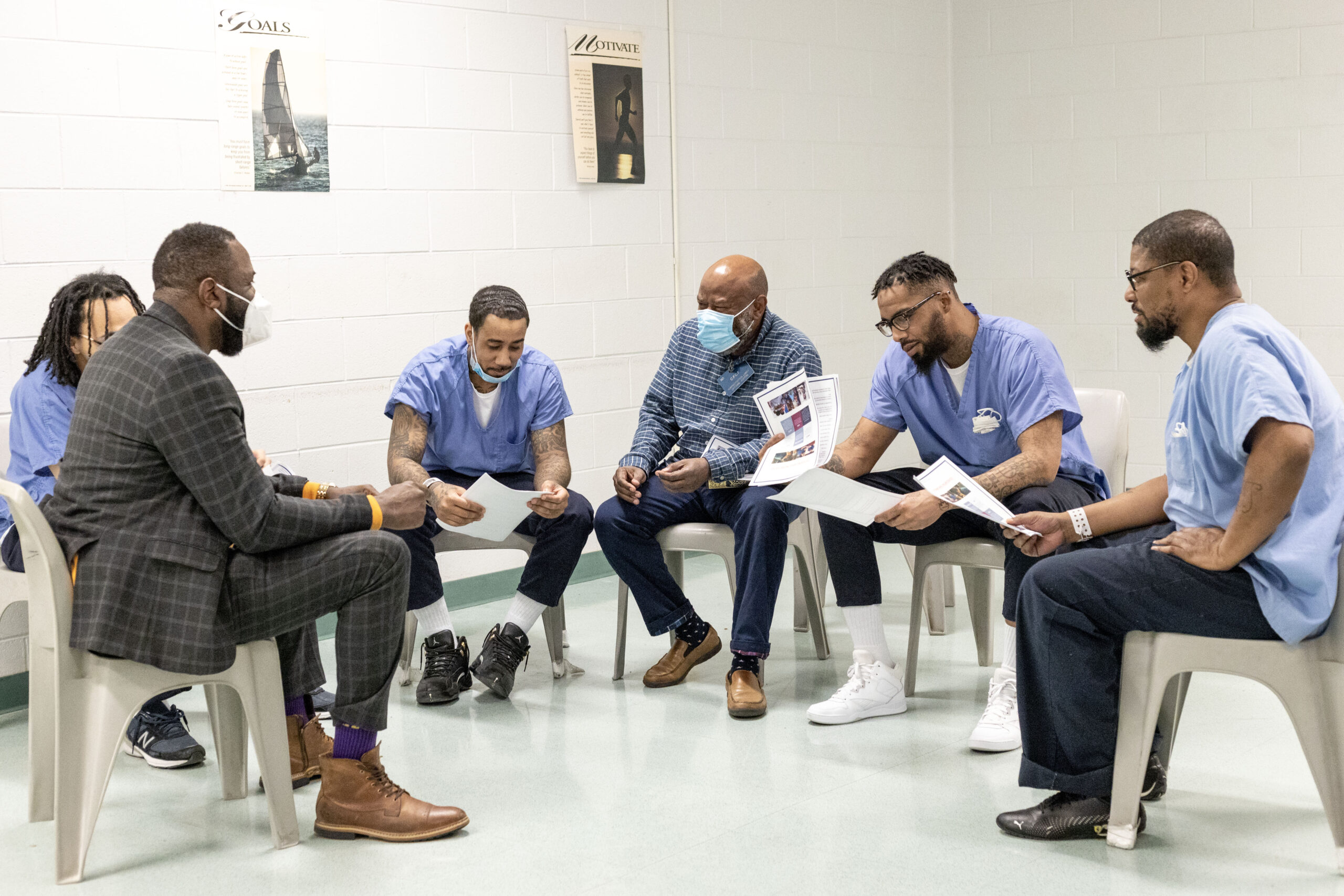

Today, similar efforts include innovative ventures into parental training for fathers at Curran Fromhold Correctional Facility in Philadelphia.

Nestled in the tight security of the prison, just off I-95, in Northeast Philadelphia, is one of a number of programs that have popped up over the years on the East Coast that provide parental training for inmates separated from their families.

The program, sponsored by the state Department of Human Services, has become a ray of hope for reviving relationships between incarcerated fathers and their children.

Prison programs like the one at Curran appear to be trying to break a cycle of incarceration.

Recent studies in the wake of mass incarceration have indicated that the increase in imprisonment has not reduced crime or violence in the nation and may even be worsening conditions in many black and brown communities.

According to the Prison Policy Institute, “The United States locks up 573 people per 100,000 residents (and that figure has decreased due to COVID-release policies in prisons). Some 1.9 million people are confined nationwide.”

Recent studies have indicated that one-in-nine African American children have a parent in prison, compared to one-in-57 white children.

According to a study called the Adverse Childhood Experiences [ACEs], 92 percent of all incarcerated parents are fathers, resulting in the current increase in male parental programs.

Such reports indicate that children of incarcerated parents often live in poverty and often grow up with poor physical and mental health outcomes.

Officials at penal facilities like Curran Fromhold are attempting to enlist the motivation of fatherly love among the incarcerated and formerly incarcerated to reduce crime and recidivism flowing through their institution.

By reconnecting families, officials say they have found that they can also reduce revolving doors of inmates in and out of prisons.

According to Deputy Commissioner Terrell Bagby at Curran Fromhold, parenting programs in correctional institutions such as the Parent Action Network provide incarcerated parents the skills and tools needed to be effective parents, not only while in custody, but also when they return to their families. They believe incarcerated parents should still be recognized as having a responsibility to their children to be actively involved in their children’s lives and assist with making parental decisions as much as possible.

“Children of incarcerated parents face so many challenges. Parenting programs in the Philadelphia Department of Prisons assist with lowering or removing barriers to parenting while incarcerated.” Bagby added, “You should witness the excitement of the graduation when the fathers have a formal presentation and dinner with their children and loved ones. It is the best feeling in the world and reverberates throughout the facility.”

This approach helps make it possible to be a loving and caring parent, even from behind walls.

“I learned I did not know everything…,” said Nasser Davenport, a graduate of the program at Curran in 2018. “I learned you can actually show love from jail — show that you care.”

“You can be a shoulder to cry on and you can learn to listen wisely,” said Davenport. Released several years ago, Davenport believes he has played an important role in helping his 12th-grade daughter receive acceptance letters from at least three historically black colleges and universities.

In the meantime, he and his wife are taking care of their five-year-old son, while Davenport also juggles two housekeeping jobs and a job as a tow truck driver.

“You’ve got to man up,” said Davenport. “This program helps keep contact so there is not a strain in the relationship.”

He added that parents have to stay on top of the situation. “If you’re not involved to lay the foundation. If they get [their guidance] from entertainers — Hip Hop Artists — that’s not real life,” he said as he sat in his tow truck recently listening for accident calls. “It’s entertainment. Real people get jobs. They get married. They buy a car. What rappers talk about is fake.”

Inmates in the program learn about resources available to them through the prison and the state’s Department of Human Services.

A tag team of two DHS co-facilitators, Andrew Williams and Abdul Hakim Muhammad, lead a weekly 90-minute workshop in which the men learn such things as how to co-parent amid tense relations with often estranged wives or girlfriends, how to avoid the trap of becoming too defensive and blaming others, how to handle the expected rejection by children, how to show they care even from behind plexiglass and brick walls, how and what to tell children about prison, ways to avoid it and how to increase quality contact on visits by children.

Muhammad and Williams also teach fathers to recognize non-verbal cues from children like withdrawal, problems sleeping, bad dreams, problems in school, fights, bullying, lying, dropping out, low grades, problems with drugs and alcohol as well as with the law.

The weekly sessions help inmates reclaim and reshape their lives and the lives of their children as the inmates prepare to transition back into family life.

This program has earned rave reviews – even from parents who are no longer incarcerated.

“I was crying (at the end of the program),” said Derrick Spivey, 34, a graduate of the parent training program who was released two years ago.

“The two co-facilitators [Andrew Williams and Abdul Hakim Muhammad] were like role models to me…I had a father but he never talked to me.. The [workshops] helped me out a lot…[They] taught me to open up,”

Group co-leader Williams, says in the 16 years he has co-facilitated the groups he has never had a fight break out in any of the workshops, despite the hot-button issues the group regularly tackles.

“They open up once they see you care,” he and Muhammad agreed.

That connection seems to fuel an openness to the men’s commitment to explore and develop pathways to be impactful parents to their children.